Keeping sports knowledge relevant presents an interesting challenge. Results change daily, player transfers happen, and the difference between “who won the match” and “who won the tournament” requires a bit of contextual understanding. This is exactly where Retrieval-Augmented Generation shines.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve been building “BluffSport” - it’s essentially an exercise in implementing an AI assistant knowledgeable in all things sport (inspired by Bluffball from the IT Crowd TV show). This is driven by an LLM to generate snippets of information to use in conversation, enabling the sports illiterate to join in the discourse with people in the know.

The obvious enhancement to this system is a RAG pipeline using up-to-date information retrieved from the web to augment the capabilities of a trained LLM beyond its knowledge cutoff. This post looks at what RAG is, why it makes sense and also looks at some experiments evaluating retrieval quality.

Understanding RAG

RAG - Retrieval Augmented Generation; it’s very much what it says on the tin. Retrieving data from storage in order to augment or enhance context used to generate something from a model, such as an LLM (Large Language Model) used for text generation. The crucial part is that this information need not be anything that the model was originally trained on, it may not have existed until after the training was complete, or even before that - when the training data was collected (this is what’s known as the “knowledge cutoff”).

Why Not Just Ask the LLM?

An LLM is able to generate information about things that it wasn’t trained on, but if there is no grounding in anything factual this can lead to hallucination to fill in the blanks. This could lead to incorrect statements being generated based purely on a fiction that the LLM constructs out of predictions of what could be part of a conversation.

Ask Claude about last night’s football results and it’ll politely remind you of its knowledge cutoff. Ask it to speculate anyway and you might get a plausible-sounding but entirely fabricated scoreline. Neither is particularly useful when you’re trying to sound like you watched the match.

The RAG Pipeline

The solution is to give the model access to current information at query time. In the case of BluffSport, this means sports-related media: match reports, interview transcripts, transfer news - anything that might help generate convincing banter. This data gets loaded into context alongside the user’s question, and the LLM can then generate responses grounded in actual facts rather than statistical hallucinations.

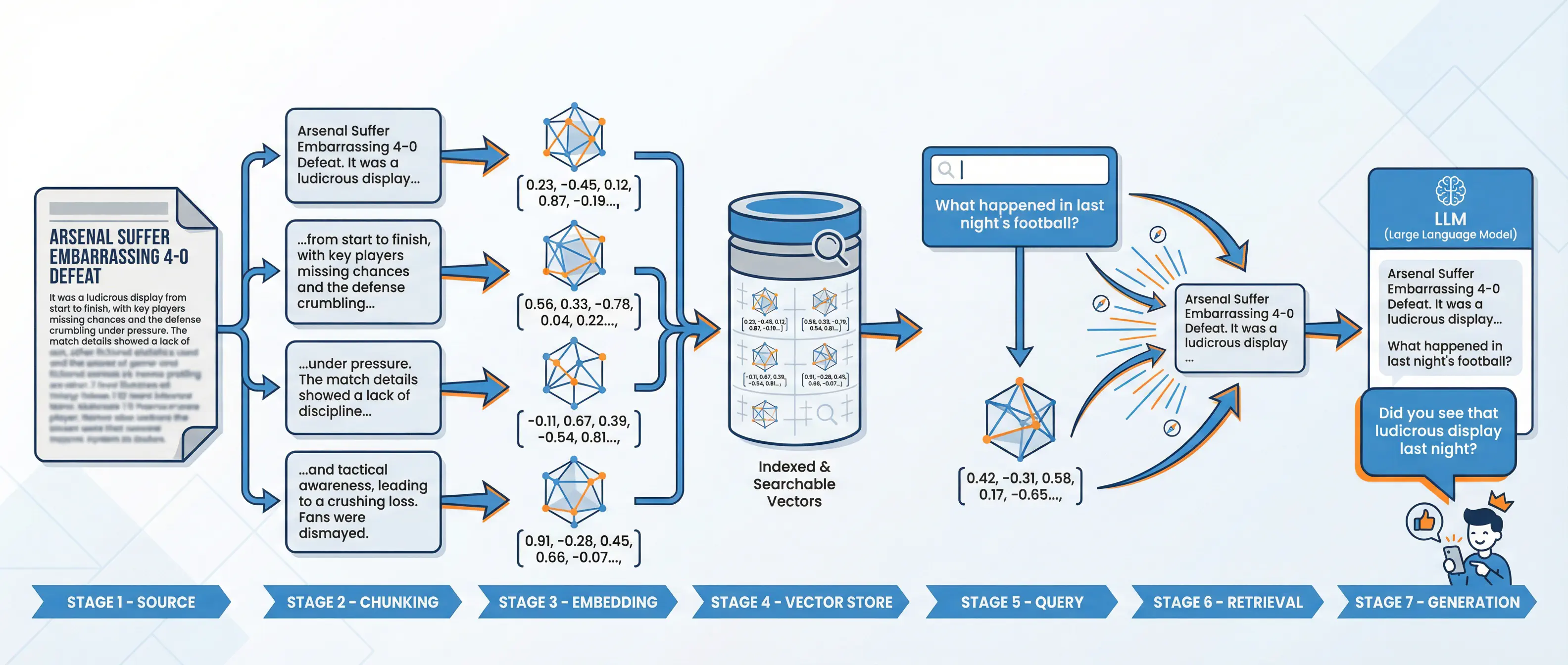

The pipeline looks something like this:

The RAG pipeline: from match reports to convincing banter

- Documents - Raw text (articles, transcripts, reports)

- Chunking - Split into searchable pieces

- Embedding - Convert text to vectors (numbers that capture meaning)

- Vector Store - Index for fast similarity search

- Query - User’s question, also embedded

- Retrieval - Find chunks similar to the query

- Generation - LLM produces response using retrieved context

RAG vs Fine-Tuning vs Prompt Stuffing

There are other ways to extend an LLM’s knowledge, each with trade-offs:

Fine-tuning involves additional training on domain-specific data. This takes time, compute resources, and needs to be repeated as information changes. For sports where results update daily (or even in real-time), fine-tuning simply can’t keep up. It makes more sense, and I’ll probably look at this in future, for stable domain knowledge - teaching a model how to talk about sport rather than what events happened. This could include alternative dialects, or even specific sports dialects (does a tennis follower use the same language as a football fan?).

Prompt stuffing means dumping all your context directly into the prompt. Simple, but it doesn’t scale. Context windows have limits, and you’re paying for tokens whether they’re relevant or not. Plus, finding the right information to stuff in the first place is the hard part.

RAG sits in the sweet spot by retrieving only what’s relevant, at query time, from an ever-updating knowledge base. The “just-in-time” nature is what makes it shine for domains like sports news.

The Implementation

I built BluffSport as a Rust library with a CLI for testing. The choice of Rust was mostly a continuation of my decision to implement the core of BluffSport backend in this language. I like Rust - its ideals and goals resonate with me, and it’s performant. I’ve always been one to prefer compile time guarantees as much as possible, and that’s exactly what Rust excels at.

Choosing the Components

For a first pass, I kept things simple:

- Embedding model: BAAI/bge-large-en-v1.5 - consistently ranks well on benchmarks, runs locally with the Rust implementation of fastembed

- Vector store: In-memory for now, just for initial testing

- Chunking: Started with fixed lengths and simple paragraph-based splitting

The library is structured around traits so components can be swapped out later - different embedding models, a proper vector database like Qdrant or pgvector, etc.

Embedding: Encoding Things

The core abstraction is an Embedder trait that converts text into vectors:

| |

It might seem redundant to define both embed_query and embed_documents as separate methods, surely they do the same thing - that’s the whole point right? But there is a reason behind this; creating the embeddings won’t actually be done manually, I will use an embedding model to do this. The one I’m using, BAAI (Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence) General Embedding (BGE) model, uses a special prompt prefix for queries to improve retrieval:

| |

This means the encoding is effectively asymmetric; queries and documents are semantically different, and the model benefits from knowing which is which.

Chunking: Breaking Things Down

I can’t just embed an entire article - embedding models have token limits (e.g. 1024 for BGE Large), and I want to retrieve specific relevant passages, not entire documents. That’s where chunking comes in. It’s as simple as it sounds, effectively breaking documents up into smaller bitesize chunks.

The Chunker trait is simple:

| |

I decided to start with two basic strategies:

Paragraph chunking splits on double newlines, respecting natural document structure. Small paragraphs get merged until they hit a minimum size.

Fixed-size chunking ignores structure entirely - just slice the text into N-character windows with some overlap to avoid cutting sentences in half.

Which works better? No idea, but that’s what experiments are for.

Vector Search: Finding Similar Things

Once I have embeddings, search is quite simple really. Since the data is now encoded as vectors within a sort of multi-dimensional space, it’s as simple as looking at distances to other points in space. Find the vectors closest to your query vector. “Closeness” is typically measured by cosine similarity - essentially the angle between two vectors.

Two vectors pointing in the same direction (i.e. similar meaning) have cosine similarity close to 1. Perpendicular vectors (and therefore unrelated) score nearer 0.

The VectorStore trait handles storage and retrieval:

| |

For now, MemoryStore just does a brute-force comparison against every stored vector. For a small sample this will work to keep my implementation simple, but in practice I’ll want something a lot more refined (nearest neighbour etc.), this would be handled by a real vector store.

Two-Stage Retrieval: Reranking

But wait, there’s more. The embedding approach above uses a bi-encoder: query and documents are encoded independently, then compared. This is fast but limited - the model never sees the query and document together.

A cross-encoder takes both query and document as input, letting the model look at both to generate an embedding. This is more accurate but much slower - and I can’t pre-compute document embeddings as I don’t know the query ahead of time (although there may be an opportunity for caching common queries).

The solution then is to do this in two-stages:

- Use the fast bi-encoder to fetch N candidates

- Use the slower cross-encoder to rerank those N candidates

- Return the top K results (sorted by rank)

| |

Then to tie it all together with a SearchEngine:

| |

Without reranking, this method would instead be implemented to just return k candidates.

The Experiments

Building the pipeline is one thing. Evaluating performance of the pipeline however is the only way to know if it’s actually working effectively, and to know if any future changes improve anything or if they are just detrimental.

Note: I’m running this on my laptop currently and hit some performance bottlenecks attempting to run evaluations on any significant amount of data. The evaluations for the purposes of this post were therefore limited to a much smaller sample of data. In reality, this needs to be scaled up to eval properly.

Evaluation

I’ve created a test set of queries against a corpus of sports articles (a small subset of the BAAI Sports Industry Corpus) - questions like “Who won the 2011 College World Series?” and “Who was the CWS Most Outstanding Player?”. Each query has a set of keywords that should appear in a relevant result.

The metrics:

- Precision@k: What fraction of the top k results are actually relevant?

- Recall@k: Did we find at least one relevant result in the top k?

- MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank): How high did the first relevant result rank? (1/rank, averaged across queries)

MRR is particularly useful - this focuses on the first result and for my intended use case the first result is what will be used, so it’s important to get that right.

Experiment 1: Chunking Strategy

I compared paragraph-based chunking against fixed-size windows of 256, 512, and 1024 characters:

| Strategy | Chunks | Precision@5 | Recall@5 | MRR | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paragraph | 30 | 0.133 | 0.533 | 0.533 | 98ms |

| Fixed 256 | 642 | 0.213 | 0.467 | 0.422 | 122ms |

| Fixed 512 | 287 | 0.240 | 0.533 | 0.500 | 105ms |

| Fixed 1024 | 136 | 0.227 | 0.533 | 0.500 | 124ms |

I’d expect smaller fixed size chunks to be more likely to align closely to a single query, and to some degree that proved correct. Fixed 512 had the best precision, though paragraph chunking had the highest MRR. The difference is subtle - paragraph chunking finds the best result faster, but fixed chunking finds more relevant results overall.

The likely explanation for this is that paragraph chunks are larger and contain more context, making the top result more likely to be comprehensive. But smaller fixed chunks are more focused, so you get more “hits” in the top 5.

Note: The paragraph chunking tests here suffered from poorly prepared sample data that resulted in entire documents as chunks (hence only 30 chunks). I restructured the samples when evaluating the LLM-as-Judge approach later on - see “Data Structure Matters” below for the dramatic difference this made.

Experiment 2: Reranking

Does the cross-encoder reranking actually help? I tested with paragraph chunking as the baseline:

| Config | n candidates | Precision@5 | Recall@5 | MRR | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No rerank | - | 0.133 | 0.533 | 0.533 | 98ms |

| Rerank | 10 | 0.120 | 0.600 | 0.547 | 4074ms |

| Rerank | 20 | 0.120 | 0.533 | 0.533 | 7210ms |

Reranking with n=10 slightly improved MRR (0.533 → 0.547) and recall (0.533 → 0.600), but at 40x the latency cost. With n=20, results were actually worse than baseline (with even more latency!).

That’s quite surprising, in theory the cross-encoder should be more accurate. But with only 30 chunks, the bi-encoder is already doing a decent job - there’s not much room for improvement, and the reranker’s different scoring function can actually reshuffle things for the worse.

Reranking likely shines more with a larger corpus of data where initial retrieval is noisier.

What the Results Mean

With 53% of queries finding a relevant result in the top position (MRR ≈ 0.53), and 53% recall, it’s doing okay but not brilliantly. Some of this could be down to the current evaluation method - keyword matching is crude and limited. Some is genuine retrieval failures.

For a production system, I’ll want these numbers higher. But for understanding the fundamentals of how this all works it has served as a useful baseline.

Modern embedding models like BGE are remarkably capable. For many use cases, the simple approach - embed and compare - might be all that’s needed. It’s certainly food for thought on whether to start off without the reranking and introduce this later while monitoring the results.

Improved Evaluation: LLM-as-Judge

Keyword matching is a bit limited. A chunk might contain all the right information but use different wording - “Fulham secured a 1-0 victory” wouldn’t match keywords looking for “won 1-0”. But what tools do we have available to evaluate arbitrary text for meaning? Oh yeah…an LLM can do that! That’s where LLM-as-judge steps in, I’ve done a quick script which achieves this using Claude via the CLI as I have that readily available to work with.

The approach is straightforward: for each retrieved chunk, ask an LLM to rate relevance on a 0-2 scale:

- 0 = Irrelevant - doesn’t help answer the query

- 1 = Partially relevant - related information but not a direct answer

- 2 = Highly relevant - directly answers or strongly supports the answer

This is more nuanced than binary keyword matching and should better reflect actual retrieval quality.

I also updated the query set to make sure that there are chunks covering different sports (football, cricket, baseball, American football) with expected answers:

| |

Running the same configurations through LLM-as-judge then revealed quite different results:

| Strategy | Reranking | Precision@5 | Recall@5 | MRR | Avg Score | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paragraph | No | 0.587 | 1.000 | 0.967 | 0.87 | 311ms |

| Fixed 512 | No | 0.613 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.91 | 123ms |

| Fixed 512 | Yes | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.956 | 0.92 | 2334ms |

The story changes significantly:

Perfect recall: Every query found at least one relevant result in the top 5. The keyword method was missing relevance that the LLM could see.

Paragraph catches up: With properly structured data (see below), paragraph chunking now achieves 59% precision with an average relevance score of 0.87 - much closer to fixed 512.

Reranking hurts MRR: The cross-encoder pushed some first-result hits down to positions 2 or 3. Its “better” understanding sometimes disagrees with what actually answers the query.

Latency cost: Reranking adds 19x latency for marginal (or negative) gains. With a small corpus where the bi-encoder is already doing well, it might not be worth the additional effort.

An MRR of ~1.0 for non-reranked configurations is encouraging - it means the top result is almost always at least partially relevant to the query. That’s exactly what you want in a RAG system where typically only the first result feeds into the LLM context.

Data Structure Matters

The paragraph chunking wasn’t quite working as well as I’d hoped, and it was clear that there was some sort of issue with low number of chunks produced. Having another look at the data I had sampled from the BAAI industry corpus I noticed I had made some mistakes. The data in it’s original form is stored as compressed JSONL archives, but in order to make it compatible with the current implementation I sampled a subset of this saving it as plain text. At this point I was not correctly separating paragraphs in the data, it might make more sense to look at improving my CLI to read in the JSONL archives directly but I don’t see this being a standard part of my application. In reality, this kind of data would be imported separately as a one off task.

So the result of this is that my initial test corpus included a large sports sample file that was essentially one massive wall of text with minimal paragraph breaks. Paragraph chunking faithfully split on \n\n, but with so few breaks, it produced just 30 giant chunks - containing entire articles of content.

The simple band-aid fix was to double up all the line endings, essentially making each line break a paragraph. After restructuring the same content, the chunk count jumped from 30 to 380, and the results changed significantly:

| Metric | Before (30 chunks) | After (380 chunks) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision@5 | 0.387 | 0.587 | +52% |

| Avg Score | 0.60 | 0.87 | +45% |

| MRR | 1.000 | 0.967 | -3% |

The precision and relevance improvements are substantial. The slight MRR drop (one query now has its first relevant result at position 2 instead of 1) seems like a fair trade for chunks that are actually focused on specific topics.

This is an important lesson: chunking strategy is only as good as your source data structure. Paragraph chunking assumes your documents have meaningful paragraph boundaries. If they don’t, you’re essentially doing whole-document retrieval - which defeats the purpose of chunking entirely.

For production use, this suggests pre-processing might be worthwhile:

- Normalise paragraph breaks in source documents

- Consider sentence-based chunking (this then doesn’t rely on the paragraph breaks, chunks would be a lot more specific, but lose their surrounding context)

- Or just use fixed-size chunking as a more robust fallback

What’s Next

This is just a small portion of the BluffSport story, there’s plenty of infrastructure work going on behind the scenes, but some other areas to explore include:

- LLM integration: Take the retrieved context and generate actual responses. This is where BluffSport becomes a conversational assistant rather than a very limited search engine.

- Scale testing: This size corpus is trivial. How does this hold up with thousands of articles? That’s when approximate nearest neighbour algorithms and proper vector databases become necessary and a proper vector store.

- Hybrid search: Combining semantic search with keyword-based scoring might get the best of both worlds.

The code is available on GitHub.